The Plan of Ayala: How One Manifesto Toppled a Presidency

The Plan of Ayala

Have you heard of the Plan of Ayala? The Plan of Ayala was more than just a dusty legal document; it was a breakup letter that changed the course of a nation. Imagine it is November 1911. The Mexican Revolution seems to be over. The dictator Porfirio Díaz has fled to Paris, and Francisco I. Madero—the man who promised democracy—is finally sitting in the presidential chair. The country is taking a collective breath, hoping for peace.

But in the southern mountains of Morelos, the guns are not silent.

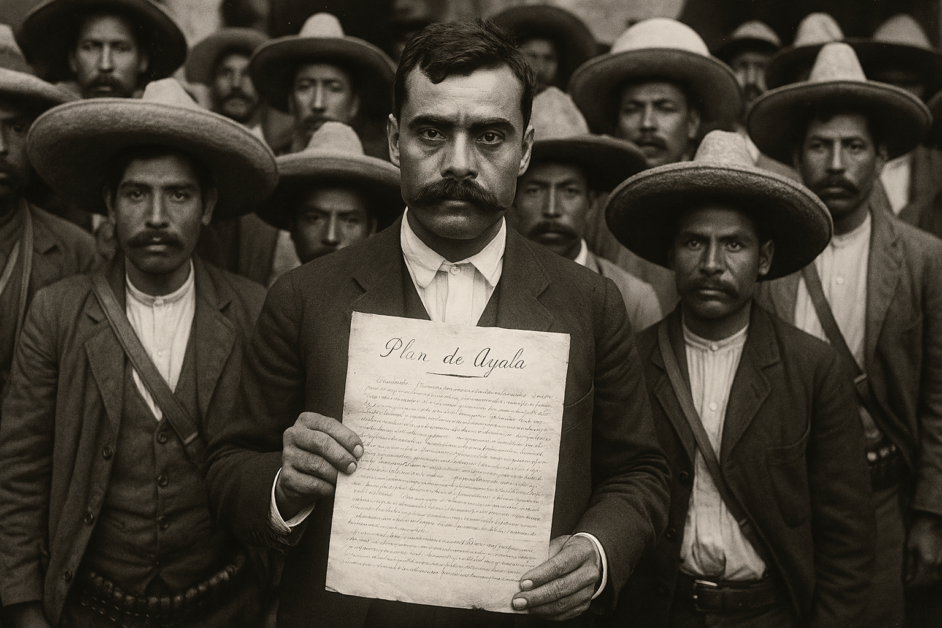

Emiliano Zapata, a village leader with a fierce mustache and an even fiercer loyalty to his people, is furious. He and his followers, known as the Zapatistas, had fought for Madero because of one specific promise: the return of village lands stolen by wealthy hacienda owners. But now that Madero is in power, that promise of agrarian reform has evaporated. Madero tells Zapata to be patient and to disarm his men. Zapata refuses.

Instead, Zapata retreats to the small town of Ayoxuxtla and drafts a manifesto that calls Madero a traitor. This document, the Plan of Ayala, did not just demand “Land and Liberty” (Tierra y Libertad); it effectively declared war on the new president. It stripped Madero of his revolutionary legitimacy and proved that the fight for Mexico’s soul was far from finished.

The Prelude: An Uneasy Alliance

To understand why Zapata felt so betrayed, we have to look back at how this whole revolution started. It began with an unlikely friendship born out of necessity.

In 1910, Francisco I. Madero, a wealthy but idealistic landowner from the north, issued the Plan of San Luis Potosí. This was the spark that ignited the revolution. In it, Madero called for Mexicans to rise up against the long-time dictator, Porfirio Díaz, promising fair elections and—crucially for Zapata—the return of lands that had been illegally taken from peasants.

For Emiliano Zapata, that last part was the only part that mattered.

Zapata wasn’t a politician; he was a horse trainer and village leader who watched his neighbors starve while wealthy hacendados (plantation owners) grew rich on stolen land. When he read Article 3 of Madero’s plan, which promised to fix these injustices, he pledged his loyalty. He believed Madero was the savior the villages of Morelos had been waiting for.

The Crack in the Foundation

Once Díaz was defeated and Madero took office, the reality set in. Madero was a man of laws and bureaucracy; Zapata was a man of action.

Madero’s View: “The war is over. We need stability. Please disarm your troops, and we will settle land disputes in court.”

Zapata’s View: “The war isn’t over until we get our land back. If we give up our guns now, the hacendados will crush us.”

The tension came to a head during a famous meeting in Mexico City. Madero, trying to smooth things over, allegedly offered to gift Zapata a piece of land to retire on. Zapata, insulted, reportedly stood up, struck his rifle, and told Madero that he didn’t join the revolution to become a landowner himself—he did it to get the land back for his people.

This was the moment the alliance died. Madero demanded disarmament first; Zapata demanded agrarian reform first. Neither would budge. Madero eventually sent General Victoriano Huerta to forcibly disarm the Zapatistas, proving to Zapata that the new president was just the old dictator in a different suit.

The Breaking Point: “Land and Liberty” Betrayed

If the meeting in Mexico City was the crack in the alliance, the military crackdown that followed shattered it completely. The events leading up to the Plan of Ayala show just how quickly a revolutionary hero can become a villain in the eyes of his followers.

A Clash of Worlds

The core problem was that Madero and Zapata were living in two different realities. Madero came from one of the wealthiest families in Mexico. To him, “reform” meant changing laws, filing paperwork, and trusting the courts. He honestly believed that if everyone just followed the rules, justice would eventually happen.

But for the peasants of Morelos, “eventually” wasn’t good enough. They couldn’t eat paperwork. They needed their fields to plant crops now. When Madero told them to trust the same judges and local officials who had stolen their land in the first place, it felt like a cruel joke.

Enter “The Jackal”

The situation turned violent when Madero made a fatal mistake: he sent the federal army to “restore order” in Morelos. Worse, he eventually placed the command in the hands of General Victoriano Huerta.

Huerta was a brutal military man with little sympathy for the peasants. He didn’t just try to disarm the Zapatistas; he engaged in a “scorched earth” campaign, burning villages and executing suspected rebels. For Zapata, seeing Madero sanction these attacks was the final straw. It proved that Madero had abandoned the revolutionary cause.

The Retreat to Ayoxuxtla

Realizing that peace was impossible, Zapata and his closest allies fled into the mountains near the Puebla border. They set up camp in the tiny town of Ayoxuxtla. It was here, surrounded by his tired but determined soldiers, that Zapata decided it was time to put his anger into writing.

He wasn’t just going to fight back with bullets; he was going to fight back with ideas. He needed a manifesto that would explain to the world why they were taking up arms against the President. That manifesto would become the Plan of Ayala, a document that enshrined the famous slogan associated with the movement: “Tierra y Libertad” (Land and Liberty).

Inside the Plan of Ayala: The Manifesto Deconstructed

So, what did this famous document actually say? When Zapata and his schoolteacher friend Otilio Montaño sat down to write the Plan of Ayala in that mountain shack, they didn’t mince words. They weren’t writing a polite request; they were writing a revolution.

You can read the full English text of the Plan of Ayala here courtesy of the University of New Mexico’s Latin American & Iberian Institute. Let’s break down the main points that shook the country.

The “Traitor” Clause (Article 1)

The very first thing the Plan did was drop a political bombshell. It formally withdrew recognition of Francisco I. Madero as President of the Republic.

It didn’t just say he was doing a bad job; it declared him a “traitor” to the revolution. The Plan accused Madero of climbing to power on the backs of the poor and then kicking them down once he reached the top. By declaring Madero illegitimate, Zapata made it clear that there was no going back.

The “Meat” of the Plan: Land Reform (Articles 6, 7, and 8)

This is the heart of the document. While Madero was focused on voting rights, the Plan of Ayala focused on survival. It laid out three specific ways to get land back to the people:

Restitution (Article 6): This was a demand for immediate justice. It stated that any fields, timber, or water that had been “usurped” (stolen) by the hacendados must be returned to the villages immediately. If a landlord thought he had a legal claim to the land, he would have to go to court to prove it—not the peasant.

Expropriation (Article 7): This was the radical part. The Plan declared that one-third of the land held by powerful Mexican monopolies would be taken (expropriated) to create villages and fields for the poor. The owners would be paid, but they had no choice in the matter.

Nationalization (Article 8): This was the punishment clause. It said that any landlord who opposed this Plan would lose all their property. Their goods would be “nationalized” (taken by the state) to pay for war pensions for the widows and orphans of the revolution.

From Politics to Class Warfare

Before the Plan of Ayala, the Mexican Revolution was largely about who got to sit in the presidential palace. After this document was published, the revolution changed. It wasn’t just about voting anymore; it was a class war.

Zapata’s manifesto told the peasants that they didn’t need to wait for permission from Mexico City to survive. It gave them a moral and legal framework to take back what was theirs. It transformed the Zapatista army from a group of rebels into a movement with a clear, written purpose: the permanent restoration of land to the people.

The Fallout: How it Destabilized the Presidency

The publication of the Plan of Ayala was like removing the keystone from an arch. At first, the structure stood, but the stability was gone. Madero wasn’t just fighting a military battle in the mountains of Morelos; he was fighting a battle for his own reputation, and he was losing.

Erosion of Legitimacy

The most immediate effect of the Plan was that it destroyed Madero’s image as the “Hero of the Revolution.” Before this, Madero could claim he represented the will of the people against the old regime. But when Zapata—the most famous peasant leader in the country—called him a traitor, that claim fell apart.

The Plan proved to the Mexican public that Madero could not control the country. He looked weak. In a time of revolution, weakness is dangerous. The Plan emboldened other rebels, like Pascual Orozco in the north, to launch their own uprisings. Suddenly, Madero was fighting a two-front war: Orozco in the north and Zapata in the south.

The Vacuum of Power

This chaos created a perfect storm. The conservative elites and the military, who never really liked Madero anyway, looked at the violence sparked by the Plan of Ayala and decided that Madero’s “democracy” was a failure. They believed the country needed a strong “Iron Hand” to restore order.

This sentiment is exactly what General Victoriano Huerta was waiting for.

Huerta used the ongoing instability—fueled by the Zapatista rebellion—as an excuse to stage a coup. In February 1913, during a bloody period known as the Ten Tragic Days (La Decena Trágica), Huerta betrayed Madero, arrested him, and eventually ordered his assassination.

While Zapata did not pull the trigger, his Plan of Ayala had created the political chaos that allowed the wolves to circle. It proved that a revolution that ignores its base cannot survive.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy

Francisco I. Madero may have fallen, and Emiliano Zapata was eventually assassinated in 1919, but the ideas in the Plan of Ayala did not die with them. In fact, the Plan became the blueprint for modern Mexico.

When the dust of the revolution finally settled, the victors sat down to write the Constitution of 1917. They looked at Zapata’s demands and realized they couldn’t ignore them anymore. The result was Article 27 of the Constitution, which permanently established the state’s right to redistribute land and recognized the communal land rights (ejidos) of villages.

The Plan of Ayala stands as a powerful history lesson: political change means nothing without social justice. Zapata proved that a promise broken is dangerous, but a promise kept can build a nation. His cry of “Tierra y Libertad” still echoes today, reminding us that the land belongs to those who work it with their hands.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q. Who wrote the Plan of Ayala?

A. The Plan was primarily written by Emiliano Zapata and his close advisor, the schoolteacher Otilio Montaño. They drafted it in the small town of Ayoxuxtla, Puebla, while hiding from federal troops.

Q. What was the main goal of the Plan of Ayala?

A. The main goal was agrarian reform. Specifically, it demanded the immediate return of lands taken from peasant villages by wealthy landowners (hacendados) and the expropriation of one-third of hacienda lands to be given to the poor.

Q. How was the Plan of Ayala different from the Plan of San Luis Potosí?

A. The Plan of San Luis Potosí, written by Madero, was focused on political changes like fair elections and removing the dictator Porfirio Díaz. The Plan of Ayala was focused on social changes, specifically land ownership and feeding the poor.

Q. Did the Plan of Ayala succeed?

A. In the short term, no—it led to years of bloody warfare. However, in the long term, it was a massive success. Its core demands were incorporated into the Mexican Constitution of 1917, which led to massive land redistribution in Mexico throughout the 20th century.

Q. Why did Zapata call Madero a traitor?

A. Zapata felt betrayed because Madero promised land reform to get the peasants' support during the revolution but refused to implement it once he became President. Madero demanded the Zapatistas disarm before any land issues were fixed, which Zapata saw as a betrayal of the revolutionary cause.