The Story Behind the Mexican Flag: The Legend of the Eagle and the Snake

What is the story behind the Mexican flag? Have you ever stopped to really look at the Mexican flag? It is one of the most intricate national banners in the world. While many countries opt for simple stripes or stars, Mexico’s flag features a dramatic, almost violent scene right in the center: a golden eagle perched on a prickly pear cactus, devouring a struggling rattlesnake. This isn’t just a striking design choice; it is a map of history.

That central emblem, known formally as the Mexican Coat of Arms, tells the story of an ancient prophecy that guided a wandering tribe to build one of the greatest empires the Americas had ever seen. It is the founding legend of the Aztec people (the Mexica) and the literal origin story of modern-day Mexico City.

To understand the flag, we have to look back long before the arrival of the Spanish, to a time when the great city of Tenochtitlan was nothing more than a swampy island in the middle of a lake, and a group of weary nomads were searching for a sign from their god.

The Origins of Story Behind the Mexican Flag: The People of Aztlán

To appreciate the gravity of the flag’s symbol, we must first understand who was looking for it.

Long before the Spanish conquest, the people we now call the “Aztecs” were actually a nomadic tribe known as the Mexica (pronounced Meh-shee-ka). The name “Aztec” is a much later term derived from their mythical homeland, Aztlán.

According to the Codex Boturini (also known as the Tira de la Peregrinación), one of the most vital indigenous manuscripts which you can view digitally via the Library of Congress, Aztlán was an island settlement surrounded by water. The name itself is often translated as the “Place of Whiteness” or “Place of Herons.” While historians and archaeologists have never agreed on its exact location—theories range from the American Southwest (like Utah or Arizona) to the state of Nayarit in western Mexico—it represented a place of origin that the Mexica were destined to leave behind.

The driving force behind this exodus was Huitzilopochtli, their fierce patron deity of war and the sun. In the migration legends, it was Huitzilopochtli who commanded the priests to lead the people out of Aztlán in search of a new home. In doing so, he also ordered them to change their identity. No longer were they to be known as the people of Aztlán (Aztecs); they were to be the Mexica, a distinct people chosen for a glorious destiny.

This wasn’t a brief trip. The migration lasted for roughly 200 years. They wandered through the arid deserts of northern Mesoamerica, often living as outcasts and mercenaries for other established tribes. It was a centuries-long test of faith, driven entirely by a prophecy that promised them a kingdom if they could just find one specific, seemingly impossible sign.

The Prophecy of Huitzilopochtli

The migration wasn’t aimless wandering; it was a divine scavenger hunt. The priests, led by a leader named Tenoch, received a specific vision from Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec god of Sun and War.

He told them their journey would only end when they found a very specific, almost contradictory sign: an eagle perched on a prickly pear cactus, devouring a serpent.

The Elements of the Vision

To the modern eye, this looks like a cool nature scene. To the Mexica, every element was a coded message:

The Eagle: Represented Huitzilopochtli himself and the sun. Eagles were the apex predators of the sky, symbolizing the warrior spirit.

The Nopal (Cactus): This wasn’t just vegetation; it represented the land and survival. According to the legend of Copil, the cactus had a gruesome origin. Copil was the nephew of Huitzilopochtli who tried to destroy him. Huitzilopochtli ordered Copil’s heart to be cut out and thrown into the swamps of Lake Texcoco. The prickly pear cactus (tenochtli) supposedly sprang from that very heart, marking the spot where the empire must rise.

The Snake: This is where history gets complicated. In most modern retellings, the eagle is eating a snake, representing the triumph of the sun (eagle) over the earth (snake). However, archaeologists have found that this might be a later interpretation.

The “Snake” Controversy

If you look at pre-Hispanic artifacts, such as the Teocalli of the Sacred War (a stone throne currently housed in the National Museum of Anthropology), the eagle isn’t eating a snake at all.

Instead, it is holding the Aztec glyph for war, known as the Atl-Tlachinolli (meaning “burning water”). When the Spanish arrived, they likely misinterpreted this abstract symbol as a snake, or perhaps changed it intentionally to fit a European narrative of “good conquering evil” (the eagle conquering the serpent). Regardless of the shift, the snake is now firmly embedded in the national identity.

The earliest and most famous depiction of the “official” version we know today appears in the Codex Mendoza, a fascinating manuscript created in the 1540s by Aztec scribes for the King of Spain, which details the history of the empire’s founding.

The Great Migration: A Test of Faith

The journey from Aztlán was not a direct march; it was a winding, multi-generational odyssey that lasted roughly 200 years.

When the Mexica finally arrived in the Valley of Mexico around the 13th century, they encountered a harsh reality: the “promised land” was already full. The valley was dominated by established, powerful city-states like Azcapotzalco and Culhuacan, who viewed the Mexica as Chichimecs—wild, uncultured barbarians from the north.

Without a home, the Mexica were forced to live as outcasts. They survived by serving as mercenaries for the dominant tribes, trading their prowess in battle for temporary safety.

The Place of Snakes

One of the most telling episodes of this era occurred when the ruler of Culhuacan, hoping to get rid of these troublesome warriors, granted them a piece of land called Tizaapan. It was a desolate, volcanic area crawling with venomous rattlesnakes. The ruler assumed the snakes would kill the Mexica.

Instead, the Mexica—hungry and resilient—roasted and ate the snakes. This moment of survival ironically foreshadowed the symbol they were searching for: a triumph over the serpent.

However, peace didn’t last. After a gruesome diplomatic incident (involving the sacrifice of the Culhuacan ruler’s daughter, whom the Mexica believed they were honoring as a goddess), they were violently expelled again. This time, they were pushed into the only place no one else wanted: the marshy, uninhabitable reeds in the center of Lake Texcoco.

It was here, in the mud and the water, that their journey would finally end.

Story Behind the Mexican Flag: The Discovery at Lake Texcoco

After years of wandering the marshes, hiding among the reeds, the prophecy finally materialized.

According to the chronicles, the year was 1325 AD. The Mexica priests looked out across the swampy waters of Lake Texcoco and saw it: a small, rocky island. Growing from a crevice in the rock was a prickly pear cactus, and perched triumphantly upon it was the golden eagle, wings spread, tearing at the serpent.

They had found it. The wandering was over.

They named the spot Tenochtitlan (meaning “Place of the Prickly Pear Cactus”). It is often said that the name comes from the combination of tetl (rock) and nochtli (cactus).

Building the Impossible City

The location, however, was a logistical nightmare. It was a small, muddy island with no timber, no stone, and no firm ground. But because their god had chosen this spot, they refused to move.

Instead of finding a better location, they engineered the land to fit their needs. They invented a system of chinampas (floating gardens), sinking timber piles into the lakebed and filling them with mud and vegetation to create artificial islands.

From this humble, muddy beginning rose one of the most magnificent cities in the world. By the time the Spanish arrived in 1519, Tenochtitlan was a metropolis of over 200,000 people—larger than London or Paris at the time. It was an engineering marvel of causeways, aqueducts, and pyramids, all centered around that specific rock where the eagle had landed.

That sacred spot is where they built their holiest shrine, the Templo Mayor. If you visit Mexico City today, you can see the ruins of this temple right next to the Zócalo; it is literally the spot marked by the “X” on the treasure map of the prophecy.

Story Behind the Mexican Flag: The Symbol Today

For 300 years under Spanish rule, the image of the eagle and the snake was largely suppressed, replaced by the cross and the royal crests of Spanish kings. But legends don’t die easily.

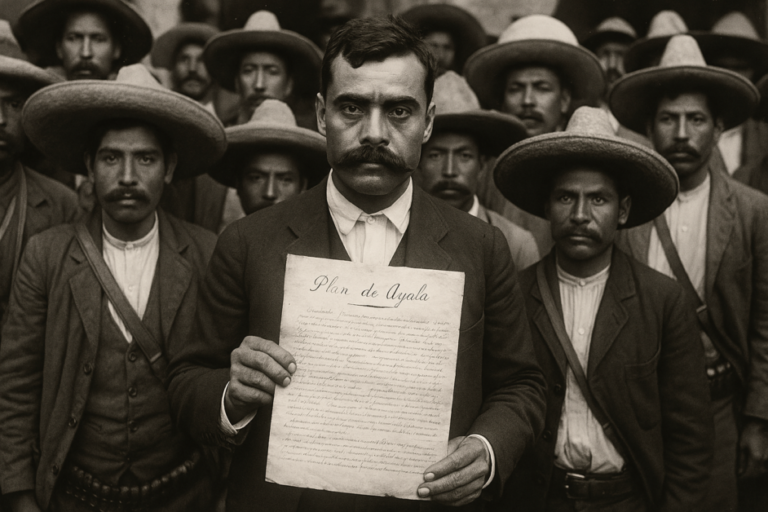

When Mexico began its fight for independence in 1810, the rebel leaders needed a symbol that would unite the people—not as subjects of Spain, but as true natives of the land. They didn’t look to Europe for inspiration; they looked back to Tenochtitlan.

Reclaiming the Past

The eagle officially became the national emblem again in 1821, when the country won its independence. The official Mexican government history details that the first flag of the independent nation was decreed by Agustín de Iturbide.

However, this first version looked slightly different from what you see today. Because Mexico was briefly established as the “First Mexican Empire,” the eagle in the center was depicted wearing a crown. When the empire fell and the republic was established in 1823, the crown was removed to symbolize freedom from royalty, and the design began to resemble the modern version we know.

The Modern Design (1968)

The flag has gone through several artistic tweaks over the centuries. The current version was officially adopted on September 16, 1968, just before Mexico City hosted the Olympic Games.

The modern coat of arms was designed by the famous Mexican artist Francisco Eppens Helguera. He redesigned the eagle to appear more aggressive and majestic, with a “profile” stance that is now the standard for all government documents and currency. You can view the historical evolution of these flags to see how the eagle transformed from a European-style heraldic bird to the fierce Aztec predator seen today.

Meaning of the Colors

While the eagle represents the ancient past, the colors of the flag—Green, White, and Red—represent the nation’s political evolution.

Originally (1821): The colors represented the “Three Guarantees” of the Army that won independence: Green for Independence, White for Religion (Catholicism), and Red for Union.

Modern Meaning: Following the secularization of the country under President Benito Juárez, the meanings changed. Today, they are widely accepted to represent:

Green: Hope

White: Unity

Red: The blood of the national heroes

Where to Experience the Legend (Travel Tips)

You can’t see Lake Texcoco in the city center anymore—it was drained and filled in centuries ago—but you can still visit the exact locations where this history took place. If you are planning a trip to Mexico City, here are the three essential stops to connect with this legend.

1. The Templo Mayor Museum

This is the most critical stop. Located just off the main square, the Templo Mayor was the main temple of the Aztec capital.

For a long time, it was thought to be lost under the modern city, but it was rediscovered by accident in 1978 by electrical workers. Archaeologists confirmed that this temple was built on the exact spot where the Mexica believed the eagle landed on the cactus. When you walk through the ruins, you are literally standing at the “X” that marked the end of their 200-year migration.

2. The National Museum of Anthropology

Widely considered one of the best museums in the world, this is where the artistic history of the symbol lives. You want to look specifically for the Teocalli of the Sacred War.

This carved stone throne (monolith) dates back to Moctezuma II’s reign and features one of the earliest depictions of the eagle perched on the cactus. It is unique because, as mentioned earlier, the eagle is shouting the symbol for war rather than eating a snake. Seeing it in person offers a fascinating glimpse into how the Aztecs viewed the symbol before the Spanish conquest.

3. The Zócalo Flag Ceremony

The Zócalo is Mexico City’s main square, built directly on top of the old Aztec island. In the very center stands a massive Mexican flag.

If you are an early riser (or hanging around at sunset), you can witness the daily military ceremony where soldiers march out from the National Palace to hoist or lower the monumental flag. Seeing the massive emblem of the eagle and snake unfurled over the ruins of Tenochtitlan is a powerful, full-circle historical moment.

Bonus Tip: To see what the “floating gardens” of Tenochtitlan actually looked like, take a trip down to Xochimilco, a UNESCO World Heritage site south of the city center. It is the last remaining network of canals and chinampas from the original lake system.

Conclusion

The Mexican flag is far more than just a colorful banner; it is a woven narrative of resilience, faith, and destiny.

Every time it is raised, it retells the story of the wandering Mexica people who refused to give up until they found their home. It reminds us that modern Mexico is built literally and metaphorically on the foundations of Tenochtitlan. The eagle, the snake, and the cactus are not just symbols of a forgotten past—they are the living heart of the country’s identity.

So, the next time you see the Mexican flag waving above a plaza or painted on the side of an airplane, take a closer look. You aren’t just looking at a national emblem; you are looking at the exact moment an empire was born.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q. Is the legend of the Mexican flag historically true?

A. While the specific details of the vision are mythological, the migration of the Mexica people is a historical fact. They did wander for centuries and eventually settled on an island in Lake Texcoco around 1325 AD. Archaeologists have confirmed that the Templo Mayor was built in the center of this settlement, aligning with the legend.

Q. What kind of eagle is on the Mexican flag?

A. The bird is typically identified as a Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), known in Spanish as the Águila Real. It is a bird of prey native to North America and was sacred to the Aztecs as a symbol of the sun.

Q. What does the cactus represent?

A. The prickly pear cactus (nopal) represents the land of Tenochtitlan. In mythology, it grew from the heart of Copil (the nephew of the god Huitzilopochtli), which was thrown into the lake. It symbolizes the heart of the empire and survival in harsh environments.

Q. Has the Mexican flag always looked like this?

A. No. While the eagle and snake have been used since independence in 1821, the artistic style has changed many times. In the mid-1800s, the eagle was sometimes depicted facing forward or wearing a crown (during the empire periods). The current version, with the eagle in profile, was adopted in 1968.