The Plan of San Luis Potosí: A Comprehensive Guide to the Spark of the Mexican Revolution

What is The Plan of San Luis Potosí?

The Plan of San Luis Potosí was much more than just a stack of papers; it was the spark that ignited the explosive conflict known as the Mexican Revolution. Imagine living in a country where the president decides to stay in power for over 30 years, and no matter how many people vote against him, he always “magically” wins. That was the reality in Mexico in 1910 under the iron-fisted rule of Porfirio Díaz, a long era of dictatorship known to historians as the Porfiriato.

For decades, Mexico seemed stable and modern on the outside, but underneath, regular people were suffering and desperate for change. Enter Francisco I. Madero, an unlikely hero who had finally had enough of the corruption and fake elections. He wrote this daring manifesto to call out the government and demand a return to real democracy.

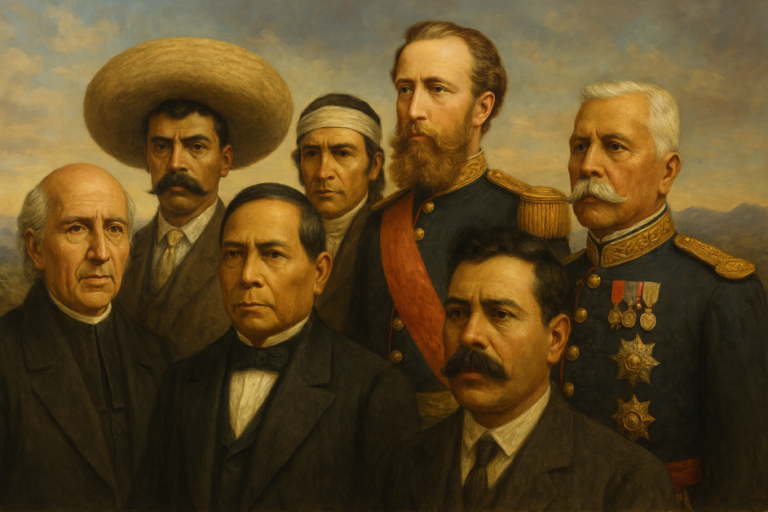

But Madero didn’t just complain; he did something incredibly risky. He set a specific date and time for the Mexican people to grab their weapons and rise up. In this guide, we are going to break down exactly how the Plan of San Luis Potosí turned a political dispute into a ten-year struggle that changed North America forever. We’ll look at the promises Madero made, and how this one document opened the door for legendary revolutionaries like Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata to take the stage.

Historical Context: The Long Shadow of Porfirio Díaz

To understand why the Plan of San Luis Potosí was such a big deal, you first have to understand the man it was written against: Porfirio Díaz.

Díaz was a military hero who took control of Mexico in 1876. For the next 30+ years, he ruled with a style often called “Pan o Palo” (Bread or the Stick). Basically, if you supported him, you got rewarded (bread); if you opposed him, you got punished (the stick). This era, known as the Porfiriato, was a confusing time. On the surface, Mexico looked great to the outside world—Díaz built thousands of miles of railroads, modernized cities, and attracted foreign businesses. But the cost was huge. The vast majority of Mexicans were poor peasants who had lost their land to wealthy hacienda owners, and they had zero say in their government.

The Interview That Changed Everything

In 1908, something unexpected happened. Díaz sat down for an interview with an American journalist named James Creelman. Perhaps trying to impress the U.S. audience, Díaz casually mentioned that Mexico was finally “ready for democracy” and that he would not run for re-election in 1910.

You can read more about this famous Creelman Interview here.

This interview was like opening a floodgate. Opposition parties that had been hiding for decades suddenly sprang to life, believing the dictator was finally stepping down. The most popular challenger was Francisco I. Madero, who toured the country drawing massive crowds with his message of change.

The Broken Promise But when the 1910 Election rolled around, Díaz changed his mind. He realized he didn’t actually want to give up power. He broke his promise, had Madero thrown in jail, and rigged the election to win another term. It was this betrayal that proved to everyone that peaceful change was impossible, setting the stage for Madero’s radical Plan of San Luis Potosí.

The Architect: Who Was Francisco I. Madero?

You might picture a revolutionary leader as a tough, gun-toting soldier wearing ammunition belts across his chest. But Francisco I. Madero was actually the complete opposite. He was a wealthy landowner from northern Mexico, a vegetarian, and a gentle intellectual who reportedly believed in spiritualism. He wasn’t initially fighting for money or power—he was fighting for an ideal.

Madero wasn’t trying to destroy the government at first; he just wanted fair play. He wrote a famous book called The Presidential Succession in 1910, which criticized Díaz and called for honest elections. This book made him a superstar among the people but a threat to the dictator.

The Great Escape

As we mentioned, Díaz had Madero arrested in the city of San Luis Potosí during the election. But Madero didn’t stay locked up for long. His wealthy family helped post bail, and he was allowed to move freely around the city during the day. Seizing his chance, he disguised himself as a railroad worker and escaped on a train heading north to the United States.

The “Texas” Plan?

Here is a cool historical secret: Although it is famous as the Plan of San Luis Potosí, Madero actually wrote and finalized the document while hiding out in San Antonio, Texas.

Why name it after San Luis Potosí? Madero dated the document “October 5, 1910” (the last day he was in San Luis Potosí) to make it look like he wrote it on Mexican soil. This was a smart legal move to avoid getting in trouble with U.S. neutrality laws, which forbade plotting foreign wars from American territory. You can read more about Madero’s exile and the rise of his movement in this exhibition by the Library of Congress.

From his safe house in San Antonio, Madero declared the recent elections illegal and named himself the “Provisional President” of Mexico. The stage was set.

Deconstructing the Plan: Key Provisions

So, what exactly did this famous document say? It wasn’t just a rant against the president; it was a legal argument and a battle plan rolled into one. Think of it as a “Terms and Conditions” update for the entire country—one that everyone had to agree to, or else.

The Core Slogan: “Sufragio Efectivo, No Reelección”

This is the most famous phrase in modern Mexican history, translating to “Effective Suffrage, No Re-election.” In simple terms: “Real votes, and no presidents for life.” Madero made this the rallying cry of the revolution. He argued that since the election was rigged, the people’s votes didn’t count, and therefore Díaz had no right to stay in power.

The Three Main Pillars

The plan had a few specific demands that you can read in the full text here, but here are the three big ones that mattered most:

Nullification of Elections: Madero declared the 1910 elections illegal. He basically hit the “delete” button on the results that kept Díaz in power.

Provisional Presidency: Since the election was void, Madero declared himself the “Provisional President” until a real, fair election could be held.

The Call to Arms: This was the scary part. Madero didn’t just ask for a protest; he set a specific date for war. He commanded all citizens to rise up in arms at 6:00 PM on Sunday, November 20, 1910.

The “Fine Print” That Changed History

There was one small section—Article 3—that Madero probably thought was a minor detail, but it ended up being huge. In it, he promised to look into the cases of peasants who had their land “arbitrarily” taken away by the wealthy.

To Madero, this was just about legal fairness. But to leaders like Emiliano Zapata in the south, this was a promise to return the land to the people. You can learn more about how this specific promise mobilized the rural poor in this analysis by the Library of Congress. This “fine print” is what turned a political dispute into a massive social revolution.

The Spark: November 20, 1910

The Plan of San Luis Potosí was unique because it didn’t just ask for change—it set a literal deadline. Madero basically set an alarm clock for the revolution: Sunday, November 20, 1910, at 6:00 PM.

Madero expected a massive, coordinated uprising. He even traveled to the border, ready to march triumphantly into Mexico to lead his army. But when 6:00 PM rolled around… almost nobody showed up. At first, it looked like a total embarrassment. Madero actually went back to the U.S. thinking the plan had failed.

The Snowball Effect

But while there wasn’t one giant army, small fires were starting to burn all over the country. The Plan of San Luis Potosí had reached the hands of tough, local leaders who were ready to fight, just not in the organized way Madero imagined.

In the North (Chihuahua): A bandit-turned-general named Pancho Villa and a muleteer named Pascual Orozco gathered armies of cowboys, miners, and railroad workers. They were experts at guerrilla warfare and quickly started defeating Díaz’s federal troops. You can read more about Pancho Villa’s legendary role here.

In the South (Morelos): A village leader named Emiliano Zapata read Madero’s plan and saw the promise to return land to the peasants (that “fine print” we mentioned earlier). He mobilized the rural farmers to fight for their fields.

Overwhelming the Dictator

These separate groups didn’t always get along, but they had a common enemy. By early 1911, these “tigers” (as Díaz later called them) were unleashing chaos. The sturdy, professional Federal Army was used to fighting traditional battles, not chasing cowboys and farmers through mountains and jungles. The Plan of San Luis Potosí had successfully turned the entire country into a battlefield that Díaz could no longer control.

The Aftermath: Success and Tragedy

Incredibly, the plan actually worked.

The call to arms in the Plan of San Luis Potosí sparked uprisings that the government couldn’t stop. Within six months, rebel forces captured the key city of Ciudad Juárez. Porfirio Díaz, realizing he had lost control, signed a peace deal called the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez in May 1911. You can read the details of this historic agreement on the Emerson Kent History Archive.

Díaz resigned and fled to Paris, famously warning that Madero had “unleashed a tiger” that he wouldn’t be able to tame.

Madero’s Critical Mistakes

Francisco I. Madero was elected president in a landslide, but his troubles were just beginning. While he was a great idealist, he struggled to manage the country’s deep social problems. He made two major errors:

He kept the old army: Madero allowed the generals who had served the dictator to keep their jobs, hoping to win their loyalty.

He delayed land reform: He told peasant leaders to wait for the courts to settle land disputes legally. This angered revolutionaries like Emiliano Zapata, who refused to disarm. Zapata eventually declared Madero a traitor in his own manifesto, the Plan of Ayala, which demanded immediate land redistribution for farmers.

The Ten Tragic Days

The end of Madero’s presidency was swift and violent. In February 1913, a coup broke out in Mexico City. For ten bloody days, artillery pounded the city streets in an event known as La Decena Trágica (The Ten Tragic Days).

Madero was betrayed by his own general, Victoriano Huerta, who had him arrested and assassinated. This event marked the failure of Madero’s peaceful democracy, but it didn’t stop the revolution. Instead, it plunged Mexico into years of deeper civil war. You can explore a detailed timeline of these battles in this interactive map by the Library of Congress.

Conclusion

The Plan of San Luis Potosí achieved its main goal: it ended the 30-year dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. But, as we’ve seen, it also opened a “Pandora’s Box” of revolution that lasted for a decade.

While Madero’s presidency ended in tragedy, his vision didn’t die with him. The revolution he started eventually led to the Constitution of 1917. This document is still used in Mexico today and includes many of the rights Madero, Zapata, and Villa fought for—like free education, workers’ rights, and ownership of land.

Today, November 20th is celebrated every year in Mexico as Revolution Day. It all goes back to that one daring document, written by an underdog who believed that even a powerful dictator could be taken down by the will of the people.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What was the main purpose of the Plan of San Luis Potosí?

A: The main purpose was to declare the 1910 elections illegal (null and void) and to call for an armed uprising to overthrow dictator Porfirio Díaz. Madero wanted to install a temporary government that would hold real, free elections.

Q: Was the Plan of San Luis Potosí actually written in Mexico?

A: No! This is a fun fact for history buffs. Francisco I. Madero wrote and finalized the plan while hiding in San Antonio, Texas. He dated it "October 5" (the last day he was in the Mexican city of San Luis Potosí) to avoid breaking U.S. neutrality laws that forbade plotting wars from American soil.

Q: Did the uprising actually happen on November 20th?

A: Sort of. Madero called for a nationwide uprising at 6:00 PM on November 20, 1910. While there wasn't a giant, coordinated army attack at that exact minute, scattered rebellions did start breaking out across the country on that date, which eventually grew into the full-scale Mexican Revolution.

Q: How is the Plan of San Luis Potosí different from the Plan of Ayala?

A: The Plan of San Luis Potosí (written by Madero) focused on political changes, like voting and democracy. The Plan of Ayala (written later by Emiliano Zapata) focused on social changes, specifically taking land back from wealthy owners and giving it to peasant farmers.

Q: Who were the key figures involved with the Plan?

A:

Francisco I. Madero: The author of the plan.

Porfirio Díaz: The dictator the plan was trying to remove.

Pancho Villa & Pascual Orozco: Leaders in the north who answered the call to arms.

Emiliano Zapata: The leader in the south who joined the fight (though he later disagreed with Madero).