Little‑Known Versions of the Mexican Flag Through History

How many versions of the mexican flag are there? Let’s find out. National flags often feel timeless, as if they’ve always existed in the form we know today. But in reality, they evolve—sometimes subtly, sometimes dramatically—reflecting political upheavals, shifting identities, and the ambitions of those in power. Few countries illustrate this better than Mexico.

While most people recognize the modern green‑white‑red tricolor with its eagle, serpent, and nopal, the path to that design is far more complex than textbooks suggest. Across empires, republics, revolutions, and regional uprisings, Mexico has flown dozens of flags—some official, others improvised, many now forgotten outside of archives and museums. These little‑known versions reveal a layered story of nation‑building, contested authority, and cultural symbolism that continues to shape Mexico’s identity today.

This article explores those overlooked chapters: the insurgent banners that sparked independence, the imperial standards that briefly reshaped the nation, the transitional republican eagles that almost vanished from record, and the revolutionary flags that flickered into existence during moments of chaos. Together, they form a visual timeline of a country constantly redefining itself.

Before Independence: Early Symbols That Pre‑Date the Flag

Long before Mexico adopted any tricolor banner, the region’s identity was expressed through powerful visual symbols rooted in Indigenous cosmology and later reshaped by colonial rule. These early emblems are not “flags” in the modern sense, but they form the symbolic foundation from which Mexico’s national imagery eventually emerged.

The Mexica (Aztec) Emblem: Eagle, Cactus, and Serpent

The most enduring pre‑independence symbol is the Mexica depiction of an eagle perched on a nopal cactus, often shown grasping a serpent. This image originates from the founding myth of Tenochtitlan, recorded in early codices such as the Codex Mendoza and Codex Azcatitlan. You can view high‑resolution scans of these codices through the Biblioteca Digital Mundial (World Digital Library):

The Mexica emblem was not a flag but a glyph, used in manuscripts, shields, and architectural carvings. Its meaning was deeply geographic and spiritual: the eagle marked the prophesied site where the Mexica would build their capital. This symbol later became the conceptual ancestor of the modern Mexican coat of arms.

Spanish Colonial Banners in New Spain

From 1521 to 1821, the territory of New Spain flew the Royal Standard of Castile and León, featuring the iconic castle‑and‑lion heraldry. A verified example is preserved by Spain’s Patrimonio Nacional.

These banners represented the authority of the Spanish Crown rather than any local identity. They were used in government buildings, military parades, and religious processions, but they never resonated as symbols of the land itself.

Early Insurgent Imagery (Pre‑Flag Independence Movements)

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, dissatisfaction with colonial rule produced a wave of local symbols—many religious, some regional, all unofficial. These included:

- Banners depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe, later used by Miguel Hidalgo in 1810

- Local militia standards featuring saints, crosses, or regional coats of arms

- Proto‑national symbols blending Indigenous and Catholic iconography

A curated collection of early insurgent banners is available through Mexico’s Museo Nacional de Historia (Castillo de Chapultepec):

These early symbols show how identity was shifting long before a national flag existed.

The 1810–1821 Insurgent Banners (Rarely Discussed)

The first Mexican flags weren’t national standards—they were insurgent banners carried by revolutionaries fighting Spanish colonial rule. These early designs were often improvised, symbolic, and deeply personal to the leaders who wielded them. Though rarely seen today, they represent the earliest visual attempts to define a Mexican identity.

Hidalgo’s Banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe (1810)

When Miguel Hidalgo launched the independence movement with the Grito de Dolores in September 1810, he carried a banner depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico’s most revered religious figure. This was a strategic choice: the Virgin symbolized unity, divine protection, and resistance to Spanish oppression. The banner itself was likely taken from a local church and repurposed as a rallying standard.

You can view a verified reconstruction and historical analysis of this banner on CRW Flags. The original is preserved in Mexico City’s Museo Nacional de Historia, though its condition is fragile.

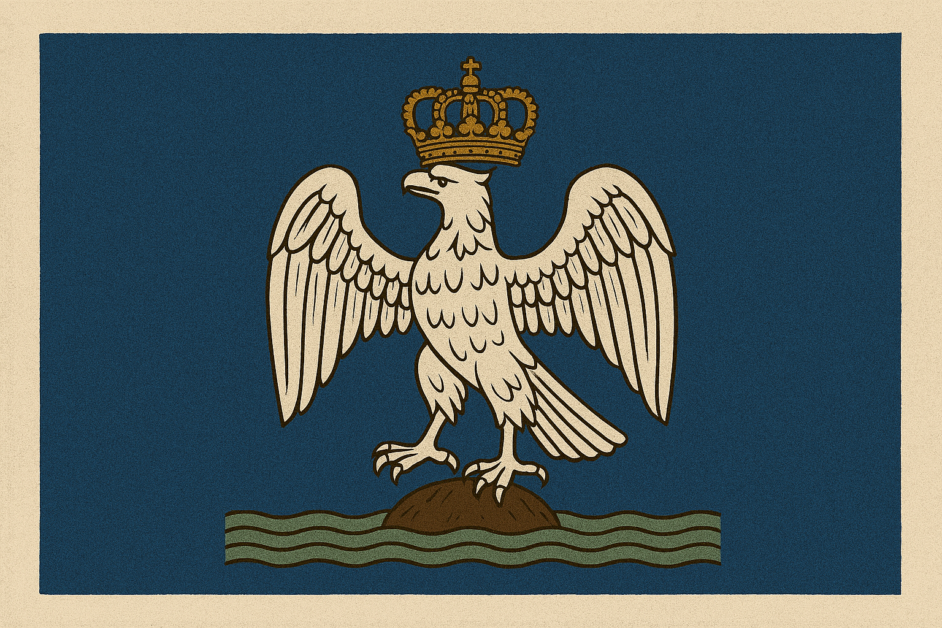

Morelos’ Blue‑and‑White Flag with Crowned Eagle (1811–1813)

José María Morelos, another key insurgent leader, introduced a more structured flag design: a blue field with a white crowned eagle, sometimes shown holding a cross or perched on a cactus. This flag symbolized sovereignty and divine justice, blending European heraldry with Indigenous symbolism.

Morelos’ flag was used by his forces in southern Mexico and is documented in the book México y sus símbolos by Carmen G. Basurto. A variant version is archived on Wikimedia Commons and discussed in detail on CRW Flags.

Regional and Factional Flags

Other insurgent groups used improvised standards—some featuring saints, crosses, or local coats of arms. These were rarely standardized and often disappeared after brief use. However, they reflect the fragmented nature of the independence movement and the diversity of regional identities.

For a broader historical overview, the Wikipedia entry on the Mexican War of Independence offers a well‑sourced summary of the key figures and events. You can also explore the History.com article for a narrative account of the war’s causes and effects.

The First Empire (1821–1823): Early Tricolor Experiments

After a decade of insurgency, Mexico achieved independence in 1821 under the leadership of Agustín de Iturbide, who briefly ruled as Emperor Agustín I. This short-lived monarchy introduced the first official tricolor flag, laying the foundation for the modern design—but with key differences that reflected imperial ambitions.

The Tricolor of the First Mexican Empire

The imperial flag adopted in 1821 featured vertical bands of green, white, and red, similar to today’s layout. However, the central emblem was distinct: a crowned eagle perched on a cactus, often shown without a serpent. The crown symbolized monarchical authority, and the eagle’s posture was more heraldic than naturalistic.

You can view a verified reconstruction of this flag on CRW Flags, which documents the evolution of Mexico’s national symbols. The original design was influenced by European tricolor models, especially the French flag, but adapted to Mexican iconography.

Military and Ceremonial Variants

During the empire, various regiments used modified versions of the flag—some with ornate wreaths, others with stylized eagles or additional heraldic flourishes. These were not standardized and often reflected the preferences of individual commanders or regions.

The Museo Nacional de las Intervenciones in Mexico City holds several preserved examples of these military standards. You can explore their collection through the INAH portal.

Why the Empire’s Flag Was Short-Lived

The First Mexican Empire collapsed in 1823, just two years after its founding. Republican forces rejected monarchical symbolism, and the crowned eagle was removed in favor of a more secular, republican design. However, the tricolor layout remained—a testament to its enduring appeal.

For a detailed timeline of Mexico’s early flags, the Mexican Government’s official history site offers a well-sourced overview.

The First Republic (1823–1864): Transitional Eagles Few People Know

After the fall of the First Empire, Mexico entered its republican phase—ushering in a new era of national symbolism. The tricolor layout remained, but the imperial crown was removed, and the eagle began a long evolution toward the modern coat of arms. These early republican flags are rarely discussed, yet they reveal how Mexico struggled to define its identity in the wake of monarchy.

The 1823 Republican Eagle

The first official flag of the republic retained the green‑white‑red vertical stripes, but replaced the crowned eagle with a naturalistic eagle perched on a cactus, devouring a serpent. This version was inspired by the founding myth of Tenochtitlan, but rendered in a more European style, often surrounded by a wreath of oak and laurel.

You can view a verified image of this flag on Wikimedia Commons. It marked the beginning of Mexico’s secular national symbolism.

State-Level and Military Variants

During this period, various Mexican states and military units adopted their own versions of the eagle emblem. Some featured stylized feathers, others added scrolls or religious symbols. These flags were not standardized and often reflected local artistic traditions.

The evolution of these designs is documented in detail on CRW Flags, which includes reconstructions and historical notes from museum archives.

Why These Flags Are Overlooked

Unlike the imperial or revolutionary banners, these republican flags were used during a time of relative institutional development. They lacked the dramatic flair of insurgent symbols and were gradually refined over decades. As a result, many transitional designs were quietly retired and forgotten.

For a broader visual timeline, the site banderademexico.net offers a chronological gallery of Mexico’s flags.

The Second Empire (1864–1867): Maximilian’s Ornate Heraldic Flags

In the mid‑19th century, Mexico briefly returned to monarchy under Emperor Maximilian I, installed by French forces and backed by conservative elites. This Second Empire introduced a radically different flag—one that reflected European heraldic traditions rather than Indigenous or republican symbolism.

Maximilian’s Imperial Coat of Arms

The imperial flag featured a black double‑headed eagle—a nod to the Habsburg dynasty—adorned with a golden crown and surrounded by elaborate heraldic elements. The eagle held a sword and scepter, and its chest bore a shield with the Mexican tricolor and crowned eagle. This design was used on ceremonial standards, military flags, and government seals.

You can view a verified reconstruction of this flag on Wikimedia Commons, and a detailed heraldic breakdown on CRW Flags.

Ceremonial and Court Variants

Maximilian’s court used ornate flags for parades, diplomatic events, and palace decoration. These often included gold embroidery, imperial monograms, and stylized wreaths. While few physical examples survive, illustrations and museum records show how these flags diverged from Mexico’s earlier nationalist designs.

The Museo Nacional de Historia and Archivo General de la Nación hold rare documents and sketches from this period. You can explore their collections via INAH’s digital archive.

Why These Designs Were Erased

After Maximilian’s execution in 1867, the empire’s symbols were purged. Republican forces viewed them as foreign impositions, and the double‑headed eagle was replaced with the single eagle of Tenochtitlan. Today, Maximilian’s flags are studied more as historical curiosities than national emblems.

For a broader context on the Second Empire’s political and visual legacy, the Encyclopedia Britannica entry on Maximilian I offers a concise overview.

The Porfirian Era (1870s–1910): Subtle but Rare Variants

Under the long presidency of Porfirio Díaz, Mexico entered a period of modernization, centralization, and visual standardization. While the national flag retained its tricolor layout and eagle emblem, subtle changes in proportions, artistic style, and ceremonial use created a series of rare variants—many of which are now overlooked.

Standardization Attempts

During the Porfirian era, the government sought to formalize the flag’s proportions and emblem placement. The eagle was rendered in a more naturalistic style, often with detailed feathers and a more dynamic posture. The serpent, cactus, and wreath were refined, but not yet standardized across all uses.

You can view a verified example of the Porfirian-era flag on Wikimedia Commons, which shows the transitional coat of arms used during this period.

Military and Naval Flags

The Mexican Navy and Army used flags with unique proportions—often longer than the standard 4:7 ratio—and sometimes included gold fringe, embroidered emblems, or regimental identifiers. These flags were used in parades, barracks, and diplomatic ceremonies, but rarely preserved.

The Museo Naval de México in Veracruz holds several examples of these ceremonial flags. You can explore their holdings via SEMAR’s official site and the museum’s virtual gallery.

Artistic Reinterpretations

During this era, artists and illustrators began experimenting with the eagle’s posture, feather detailing, and serpent orientation. These reinterpretations appeared in textbooks, government publications, and patriotic posters—but were never officially adopted.

For a visual timeline of these artistic shifts, the Banderas Históricas de México archive offers reconstructions and commentary from historians and vexillologists.

Revolutionary Period (1910–1920): Fragmented Symbolism

The Mexican Revolution was not a single movement—it was a decade-long civil war involving competing factions, each with its own vision for Mexico’s future. As a result, this period produced a wide array of non-standard flags, many of which were improvised, symbolic, and deeply tied to regional or ideological identities. These banners reflected the fractured nature of the revolution and the urgency of its causes.

Zapatista Banners: “Tierra y Libertad”

In the south, Emiliano Zapata led agrarian forces demanding land reform and Indigenous rights. His troops rallied under the stark black banner emblazoned with the phrase “TIERRA Y LIBERTAD” (“Land and Liberty”). This flag rejected centralized authority and emphasized grassroots justice. It was often hand-painted on cloth, carried in marches, and used in propaganda.

You can view a verified reconstruction of this flag on CRW Flags and in the Library of Congress’s exhibition on The Mexican Revolution and the United States.

Villista Standards: Improvised and Fierce

In the north, Pancho Villa’s forces used a mix of flags—some based on the national tricolor, others featuring skulls, rifles, or revolutionary slogans. These were often created locally and varied by battalion. One mural in Chihuahua depicts a red flag with a black skull-and-crossbones, believed to be associated with Villista cavalry.

While few physical examples survive, Villa’s banners are referenced in the Museo de la Revolución and in historical accounts compiled by the Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México (INEHRM).

Constitutionalists: Tricolor with a Republican Eagle

The Constitutionalist faction, led by Venustiano Carranza, sought to restore national unity and used more traditional flags—often the republican tricolor with eagle and serpent. However, even these varied in style and proportions, depending on the printer or region. Some featured simplified wreaths or stylized eagles with minimal detail.

A verified example of a Constitutionalist-era flag is archived on Wikimedia Commons, showing the transitional coat of arms used during Carranza’s presidency.

Why These Flags Matter

These revolutionary banners weren’t just military identifiers—they were ideological statements. They reflected the competing visions for Mexico’s future: agrarian justice, populist rebellion, and constitutional reform. Most were never standardized and disappeared after the war, but they remain powerful symbols of resistance and transformation.

The Road to the Modern Flag (1920–1968): Quiet Redesigns

After the revolution, Mexico entered a period of institutional rebuilding. The national flag was reaffirmed as the green‑white‑red tricolor with the eagle, serpent, and cactus—but the emblem underwent a series of quiet redesigns that gradually shaped the modern coat of arms.

The 1934 Eagle Redesign

In 1934, the Mexican government officially standardized the eagle emblem. The new design featured a more naturalistic eagle, perched on a cactus, devouring a serpent, and surrounded by a symmetrical wreath of oak and laurel. This version was used on flags, coins, stamps, and government documents.

You can view a verified image of this flag on Wikimedia Commons, which shows the emblem used until the next major update in 1968.

Artistic Refinements

Throughout the mid‑20th century, artists refined the eagle’s posture, feather detailing, and serpent orientation. These changes were subtle but important: they helped unify the emblem across different media and reinforced its symbolic clarity.

The Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) holds archival sketches and design documents from this period, which you can explore via INAH’s digital archive.

Military and Civic Use

During this era, the flag was widely used in schools, parades, and diplomatic missions. Variants with gold fringe, embroidered emblems, and ceremonial proportions were common, especially in military and presidential contexts.

The Museo Nacional de Historia in Mexico City preserves several examples of these mid-century flags, including those used during presidential inaugurations and Olympic ceremonies.

Why This Period Matters

The 1934–1968 flag represents the final step before the modern design. It codified the eagle’s posture, the wreath’s shape, and the serpent’s position—creating a visual identity that would endure for generations.

For a full timeline of Mexico’s flag evolution, the Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional (SEDENA) offers a detailed overview with official illustrations.

The Modern Flag (1968–Present): Codified Identity

In 1968, Mexico hosted the Olympic Games and seized the moment to officially codify its national flag and coat of arms. This marked the end of centuries of visual experimentation and the beginning of a standardized, legally protected design that remains in use today.

The 1968 Standardization

The Mexican government issued a decree that defined the precise proportions, colors, and emblem layout of the national flag. The eagle was rendered in a dynamic, naturalistic pose: wings partially spread, head turned left, beak gripping a serpent, talons clutching a cactus. The wreath of oak and laurel was symmetrically arranged and tied with a ribbon in the national colors.

You can view the official design on Wikimedia Commons and in the Mexican government’s own documentation via SEDENA.

Legal Protection and Civic Use

The flag’s design is now protected under Mexican law. It is used in schools, government buildings, military ceremonies, and international events. Variants with gold fringe or embroidered emblems are permitted for ceremonial use, but the core design must remain unchanged.

The Ley sobre el Escudo, la Bandera y el Himno Nacionales (Law on the National Coat of Arms, Flag, and Anthem) outlines the rules for display, reproduction, and respectful treatment. You can read the full legal text on DOF.gob.mx.

Symbolism and Legacy

The modern flag encapsulates centuries of history: the eagle of Tenochtitlan, the tricolor of independence, the serpent of myth, and the wreath of republican unity. It is one of the most recognized flags in the world and a powerful symbol of Mexican identity.

For a visual timeline of all historical flags, the CRW Flags Mexico archive offers reconstructions, commentary, and links to museum holdings.

Conclusion: From Glyph to Nationhood

The Mexican flag is more than a tricolor—it’s a visual archive of centuries of struggle, belief, and transformation. From the Mexica glyph of the eagle on a cactus, to the insurgent banners of Hidalgo and Morelos, to the imperial crests of Iturbide and Maximilian, and finally to the modern emblem codified in 1968, each design reflects a distinct moment in Mexico’s journey toward sovereignty and identity.

What began as a sacred prophecy became a revolutionary symbol, then a contested icon, and ultimately a unifying national standard. The eagle, serpent, and cactus endure not just as mythic imagery, but as a living emblem of resilience, diversity, and pride.

This visual history reminds us that flags are never static—they evolve with the people who carry them. Mexico’s flag tells a story of empires, republics, revolutions, and rebirths. And through every change, the heart of the symbol remains: an eagle, a cactus, and the promise of land and liberty.